-

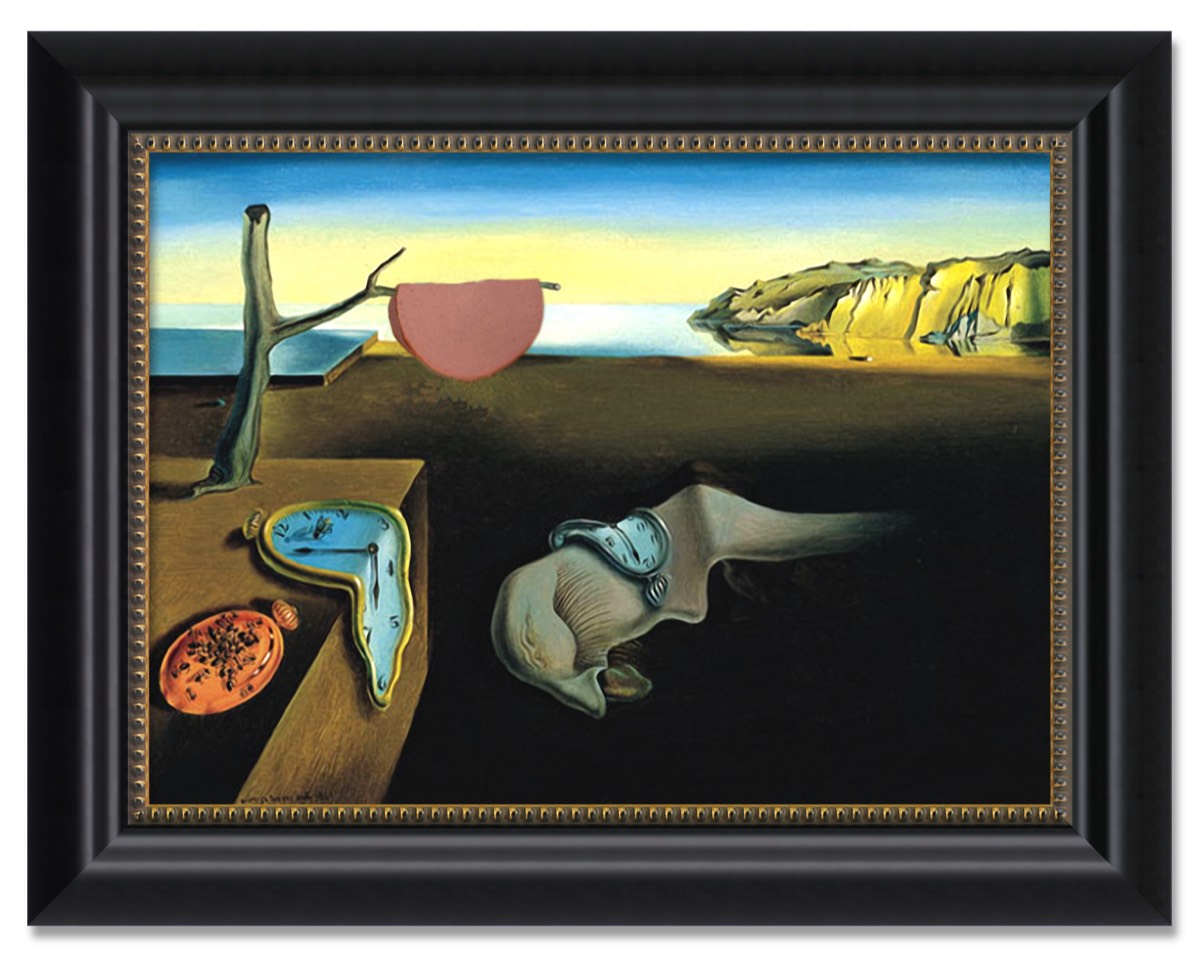

Salvador Dalí had heard enough analysis to last him a lifetime. The critics and the public were yammering about symbolism in realistic terms. Clearly they couldn’t think beyond the imagery and grasp the depth of meaning that was right in their faces.

Salvador Dalí had heard enough analysis to last him a lifetime. The critics and the public were yammering about symbolism in realistic terms. Clearly they couldn’t think beyond the imagery and grasp the depth of meaning that was right in their faces.

The ants were obvious enough and most people discerned his intentions, though some thought it was a pun about time marching on. Although people were divided about the limber watches, they were mostly on target, and some of the retorts about sexuality were quite clever, making Dalí wish he had thought of that aspect himself. “Another time,” he quipped, acknowledging the other interpretations had plausibility.

But the amorphous shape in the center of his composition proved most enigmatic and controversial. Charles Wright, an obscure critic at best, was fervent and vocal in his ridicule of anything avant-garde; Wright was a traditionalist who abhorred surrealism, cubism, any –ism save realism, and in his critique he savaged this form he didn’t recognize.

Rather than try to understand the symbolism, Wright wrote: “What is this form that Dalí foists upon us? Is it a duck’s head with some mutant bill? Or perhaps a tiny nose sewn upon a giant eyelid with eyelashes? Perhaps some unknown species newly discovered in some tropical hell? Or some hideous oyster-like apparition? Or maybe it’s just baloney! Well, baloney to Señor Salvador Dalí, I say.”

Dalí did not take these insults lightly. “Wright is wrong,” he stormed as he barged into the exhibition and tore The Persistence of Memory from the wall.

In his studio he overpainted a perfect slice of baloney on the dead tree branch. He determined to have his moment with Wright and went directly to his newspaper office.

Confronting Wright where he sat behind his desk, Dalí roared, “You idiot, you fool. If I paint baloney you will know it’s baloney. Even an untrained sewer worker can recognize the baloney on this canvas.” He slammed the newly modified canvas on Wright’s desktop sending a sheaf of papers fluttering for shelter.

“Look beyond the obvious,” he sneered, twirling his moustache. Then he snatched the painting from Wright’s hands and returned to his studio.

“Ahhhhh,” he said aloud. “This composition is actually better than the original. Ah, yesssssss, I see what I must do.” Quickly he scraped the still-wet paint away and proceeded to add another limp watch over the tree branch which had been empty before. “Now,” he exclaimed, “it’s perfect.” -

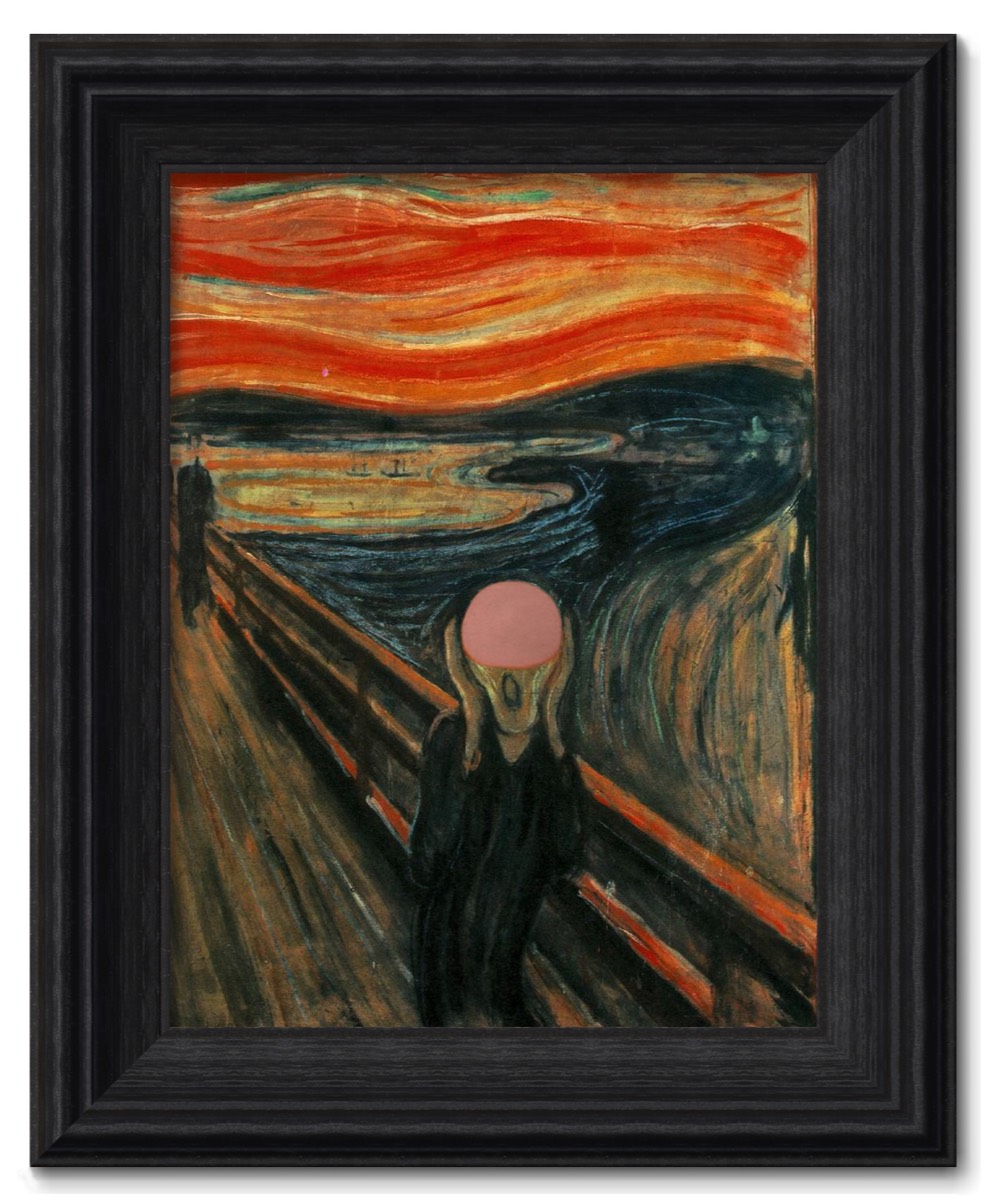

Edvard couldn’t sleep. Nor could he understand what seemed to him so bizarre that were he to continue mentioning it to any of his dwindling number of friends, they would think him mad. He began to dread handling the knives of his trade, fearful that the outbursts of rage that had begun plaguing him three months ago might further descend into violence–even murder. Edvard was a butcher, had always been a butcher and would die a butcher.

Edvard couldn’t sleep. Nor could he understand what seemed to him so bizarre that were he to continue mentioning it to any of his dwindling number of friends, they would think him mad. He began to dread handling the knives of his trade, fearful that the outbursts of rage that had begun plaguing him three months ago might further descend into violence–even murder. Edvard was a butcher, had always been a butcher and would die a butcher.

“If I can’t get some sleep, it might be better to die,” he thought testily as he locked his shop for the night. Wearily he approached his dark house with its infernal yet beguiling bed chamber. Warily he entered, lit a single candle and glumly ate his meager meal. Then lacking the will to resist the allure of sleep he fell into bed–the same bed of his torment–and began to dream.

It was an ordinary Sunday, a day nondescript except for an especially striking sunset. He walked placidly over the bridge, a bridge he crossed regularly on his Sunday walks. He enjoyed the shimmering sunlight on the water below and the sea smells—especially the scent of the sea, so different and refreshing, not like the dank, meat-laden vapors of his butcher shop.

He closed his eyes and inhaled hoping to fix the aroma in his memory when suddenly his breathing was stopped, and instead of the sea he sensed the fetor of unctuous, cold baloney.

The baloney clung to his face like a huge pink leech which he could not remove, simultaneously blinding and smothering him. He could breathe through his mouth or scream, but not together; so he screamed and awoke, clammy and doomed to wakefulness.

The next day he was describing his nightmare to his new assistant when a customer interrupted saying, “I couldn’t help but overhear your problem. Your nightmare reminds me of the work of German psychiatrist Fritz Mohr. He believes that through the creation of artwork you can confront, understand and overcome your fears.”

Edvard had enjoyed art in his student days, but his father had insisted that he come into the family business. It had been years since he had held a brush—his hand was more melded to the shape of a knife, but he bought paints, brushes and canvases, went home and painted into the night. In fact, he painted all night, and the next day he felt as refreshed as if he had slept soundly.

That very week he sold his butcher shop and decided to become a painter. Over his career he recreated that original painting many times but without the baloney. And he never had another nightmare. -

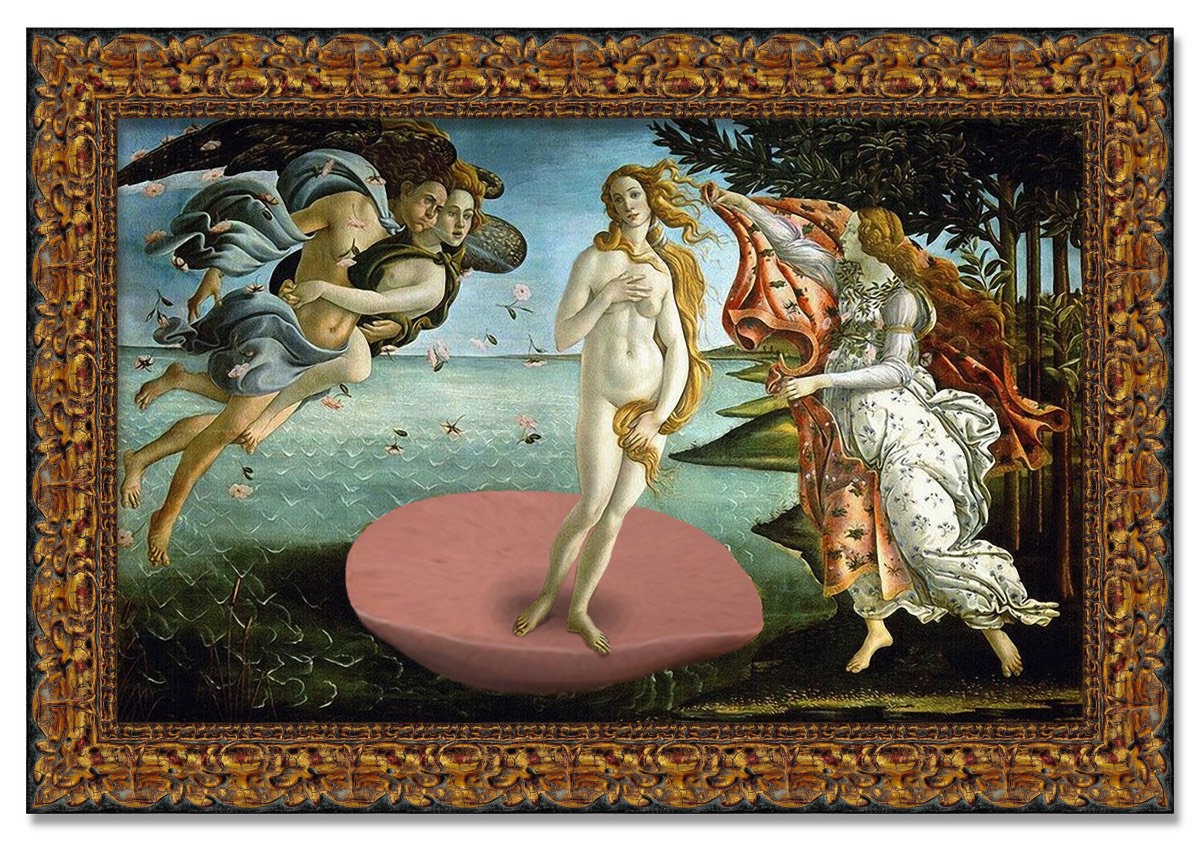

Cornelia had a problem. Hans, her sole, shy suitor, had merely alluded to a romantic interest in her; she wasn’t getting any younger; and her two younger sisters were becoming increasingly impatient with her unmarried status.

Cornelia had a problem. Hans, her sole, shy suitor, had merely alluded to a romantic interest in her; she wasn’t getting any younger; and her two younger sisters were becoming increasingly impatient with her unmarried status.

Hans was fairly well-to-do, reasonably attractive, only sixteen years her elder and could be an acceptable suitor, but only if she could loosen his tongue to the language of romance. She longed to be engaged—if not to Hans, then to someone, but soon, before time sentenced her to spinsterhood.

Hans was a pleasantly simple man, portly, slightly shy (which was suitable to her liking), socially uncomfortable (which she could reverse over time) and the eldest son in a family of successful meat merchants. Oddly, yet compellingly, he was a student not of the fine arts but of the sausage arts. Hans loved to speak of meat—its preparations and curing, its spices, the breeding of livestock for consumption, indeed the preparation of all manner of food, but on arts and romance, he fell silent.

Once he had alluded to the possibility of marriage, but suddenly and inexplicably drifted into talk of sausages, their preparation and of the construction of casings, the virtues of hard versus soft sausages, how the quality of a sausage was not in its size, how they were best enjoyed, how they were stuffed, how spices enhanced their enjoyment and on and on. Finally he became so flustered and flushed he had to excuse himself from the room. Days stretched into weeks into months with no contact whatsoever. Cornelia was ready to entertain overtures from another suitor who more shared her interests in the arts but sadly lacked funds.

“Where is the overt verbal commitment from Hans,” she thought. “Can he not see that my answer would be ‘Yes’ in spite of his quirks?” Then one day her maid appeared with an odd message, one that only she could understand–a single slice of baloney.

Although Hans had confessed his love of baloney in particular and sausages in general during that long-ago dinner conversation, she couldn’t comprehend the deeper meaning of this odd presentation, its significance in this new context. Was it a sign of affection or rejection–a marriage proposal from a meat merchant or a Dear Cornelia letter without words?

She studied the slab, pondering its unwritten message. Still, she was hungry, and with the right wine it would make a nice repast while she composed her written response.

They wed shortly thereafter, and as a token of his affection Hans commissioned this portrait to hang in their bed chamber and another, slightly different version, to hang in their drawing room. They had many children. -

Alessandro di Mariano di Vanni Filipepi had the problem most artists have–no money. So when a tavern owner from Bologna sought to commission a painting for his eatery he jumped at the opportunity. But when he heard what Giuseppe da Ponta desired, an empty belly no longer seemed so important.

Alessandro di Mariano di Vanni Filipepi had the problem most artists have–no money. So when a tavern owner from Bologna sought to commission a painting for his eatery he jumped at the opportunity. But when he heard what Giuseppe da Ponta desired, an empty belly no longer seemed so important.

Giuseppe, being a proud resident of Bologna, loved baloney. He loved it in all of its forms–pork, beef, veal or any combination thereof infused with herbs, flavored with wine, smoked or unsmoked, cold or warm–he relished baloney; Alessando, not so much.

Giuseppe had recently, quite by accident he explained, discovered something about baloney that amused and inspired him. His chef had been experimenting with thin baloney appetizers when Giuseppe threw a slice into a skillet and laughed aloud when it puffed up into what looked to him like a small breast. “We already have our Nipples of Venus truffles,” Giuseppe thought, “I’ll create Venus’ Breasts, a baloney concoction flavored and prepared like no other.”

Saying thus he swore Alessandro to secrecy about his still unfinalized chef-d’oeuvre while slyly commenting that he was certain that he also would not betray what he was certain would be Alessandro’s chef-d’oeuvre. They quickly agreed on the size of the work, the price and a delivery date, and Alessando set to work.

In three month’s time it was done and considering the demands, Alessando was somewhat pleased with the result. “What is it about patrons that makes them want to appear in the work or control the artist’s hand,” he mused as he carefully wrapped his newest painting. It would take days to reach the tavern, but enough lira had been advanced that he had the funds to hire transport and acquire lodging on the trip to Bologna where he would collect the balance owed.

Giuseppe’s directions were clear, and Alessandro’s arrival was timely, yet regrettably too late; for Giuseppe had passed away a week prior. His eldest son, the new proprietor, scorned the painting and refused delivery and any further payment. So Alessandro now owned a canvas full of baloney which he prayed he would one day be able to sell even if he had to make alterations.

“Perhaps a seafood merchant would be interested,” he mused. “Yes,” he smiled, contemplating his next move. After being denied the remainder of his fee he vowed to never let himself be held over a barrel again and that day changed his name to Sandro Botticelli. The rest is art history. -

ACT ONE

ACT ONE

Two rooms set up side by side, 2 chairs each, small table or stand, lights. A

knitting basket and baskets of magazines and books are nearby. The room

on LEFT is less ornate.

Clothing is turn of the century vintage, class specific.

A sign on RIGHT in front of rooms bears the Hadleyburg Seal and Motto,

“Lead Us Not Into Temptation”

NARRATOR sits LEFT FRONT

MRS. RICHARDS is seated on LEFT REAR reading a newspaper as the

narration begins. THE STRANGER slowly drags sack through audience

past sign until he is OFF STAGE REAR RIGHT awaiting knock.

NARRATOR: It was many years ago. Hadleyburg was the most honest and upright town in all the region round about. It had kept that reputation unsmirched

for three generations, and was prouder of it than of any other of its

possessions. It was so proud of it, and so anxious to insure its perpetuation,

that it began to teach the principles of honest dealing to its babies

in the cradle, and made the like teachings the staple of their culture

thenceforward through all the years devoted to their education. Also,

throughout the formative years temptations were kept out of the way of

the young people, so that their honesty could have every chance to harden

and solidify, and become a part of their very bone. The neighboring

towns were jealous of this honorable supremacy, and affected to sneer

at Hadleyburg’s pride in it and call it vanity; but all the same they were

obliged to acknowledge that Hadleyburg was in reality an incorruptible

town; and if pressed they would also acknowledge that the mere fact that

a young man hailed from Hadleyburg was all the recommendation he

needed when he went forth from his natal town to seek for responsible

employment.

But at last, in the drift of time, Hadleyburg had the ill luck to offend a

passing stranger–possibly without knowing it, certainly without caring,

for Hadleyburg was sufficient unto itself, and cared not a rap for strangers

or their opinions. Still, it would have been well to make an exception in

this one’s case, for he was a bitter man, and revengeful. All through his

wanderings during a whole year he kept his injury in mind, and gave all

his leisure moments to trying to invent a compensating satisfaction for

it. He contrived many plans, and all of them were good, but none of them

was quite sweeping enough: the poorest of them would hurt a great many

individuals, but what he wanted was a plan which would comprehend the

entire town, and not let so much as one person escape unhurt. At last he

had a fortunate idea, and when it fell into his brain it lit up his whole head

with an evil joy. He began to form a plan at once, saying to himself “That is

the thing to do–I will corrupt the town.”

Six months later he went to Hadleyburg, and arrived at the house of the old

cashier of the bank about ten at night.

DOOR KNOCK, LIGHTS UP

MRS. RICHARDS LOWERS NEWSPAPER

MRS. RICHARDS: Come in.

MAN ENTERS AND DRAGS HIS SACK INTO THE CORNER

STRANGER: Pray keep your seat, madam, I will not disturb you. There–now it is

pretty well concealed; one would hardly know it was there. Can I see

your husband a moment, madam?

MRS. RICHARDS: No, he has gone to Brixton, and might not return before morning.

STRANGER: Very well, madam, it is no matter. I merely wanted to leave that sack in his care, to be delivered to the rightful owner when he shall be found. I

am a stranger; he does not know me; I am merely passing through the

town tonight to discharge a matter which has been long in my mind.

My errand is now completed, and I go pleased and a little proud, and

you will never see me again. There is a paper attached to the sack which

will explain everything. Goodnight, madam.

HE EXITS. SHE WATCHES HIM LEAVE THEN TURNS TO SACK

AND READS NOTE ALOUD.

MRS. RICHARDS: “To be published, or, the right man sought out by private inquiry–

either will answer. This sack contains gold coin weighing a hundred and

sixty pounds four ounces!” Mercy on us, and the door not locked!

MRS. RICHARDS FLIES ALL ABOUT IN A TREMBLE AND LOCKS

DOOR.

Is that a burglar I hear? Oh my! OH MERCY!

CONTINUES READING NOTE

“I am a foreigner, and am presently going back to my own country, to

remain there permanently. I am grateful to America for what I have

received at her hands during my long stay under her flag; and to one

of her citizens–a citizen of Hadleyburg–I am especially grateful for a

great kindness done me a year or two ago. Two great kindnesses in fact.

I will explain. I was a gambler. I say I WAS. I was a ruined gambler.

I arrived in this village at night, hungry and without a penny. I asked

for help–in the dark; I was ashamed to beg in the light. I begged of the

right man. He gave me twenty dollars–that is to say, he gave me life, as I

considered it. He also gave me fortune; for out of that money I have made

myself rich at the gaming table. And finally, a remark which he made to

me has remained with me to this day, and has at last conquered me; and in

conquering has saved the remnant of my morals: I shall gamble no more.

Now I have no idea who that man was, but I want him found, and I want

him to have this money, to give away, throw away, or keep, as he pleases. It

is merely my way of testifying my gratitude to him. If I could stay, I would

find him myself; but no matter, he will be found. This is an honest town, an

incorruptible town, and I know I can trust it without fear. This man can be

identified by the remark which he made to me; I feel persuaded that he will

remember it.

“And now my plan is this: If you prefer to conduct the inquiry privately, do

so. Tell the contents of this present writing to any one who is likely to be

the right man. If he shall answer, “I am the man; the remark I made was

so-and-so,” apply the test–to wit: open the sack, and in it you will find a

sealed envelope containing that remark. If the remark mentioned by the

candidate tallies with it, give him the money, and ask no further questions,

for he is certainly the right man.

“But if you shall prefer a public inquiry, then publish this present writing

in the local paper–with these instructions added, to wit: Thirty days from

now, let the candidate appear at the town-hall at eight in the evening

(Friday), and hand his remark, in a sealed envelope, to the Rev. Mr.

Burgess (if he will be kind enough to act); and let Mr. Burgess there and

then destroy the seals of the sack, open it, and see if the remark is correct:

if correct, let the money be delivered, with my sincere gratitude, to my

benefactor thus identified.”

SITS DOWN, EXCITEDLY

What a strange thing it is! . . . And what a fortune for that kind man who

set his bread afloat upon the waters!…If it had only been my husband

that did it!–for we are so poor, so old and poor!…

SIGHS AND BEGINS WALKING TOWARD SACK -

A haiku for you

Animal language,

subtle yet discernible,

when paid attention.