We had been taking turns getting up every hour through the early spring nights to check on Tindra. Her udder had been hot and hard for a week, and her due date had come and gone.

I had come to stay with Anneliese Virro, the breeder who had sold me my three Icelandic mares. I planned to breed them, but I had never been present at a foaling. I knew I needed some first hand experience if I was going to do the best I could for my mares when their foaling times came. Seventy Icelandic foals had been born at Anneliese’s farm, so the foaling routine was well established.

As soon as a pregnant mare begins to “make a bag”–her udder begins to fill–she is moved to the foaling paddock, which is in view from the farmhouse. Lights on the house and the surrounding trees make the mare dimly visible at night but also allowed her privacy in the deep shadows of the trees. The new grass in the paddock had been eaten down to nibbles, so there was no risk of problems from fungus in the fescue. Years ago, it was determined that some fescue grass in our region of Kentucky carried a fungus that caused major problems in pregnant mares if they grazed on it during the last three months of gestation. Mother-to-be should get only fescue-free hay, minerals, and a little grain with ground flax until her foal was born.

And when would that be? Tindra was showing all the signs of imminent birth, but no foal. Then one late afternoon, she began trotting briskly from one end of the paddock to the other and sweating lightly even though the air was cool. Anneliese announced, “Tonight is the night.” We fixed dinner with one eye on Tindra, but she was now standing quietly, enjoying her hay. As dusk deepened into full dark, she finally lay down.

Her back legs stood stiffly straight from her body as she labored on her side. First, two tiny hooves emerged, one slightly behind the other, still inside a translucent white sac. Anneliese quickly tore the sac with her hand, and the amniotic fluid gushed out. Now the mare would not have to deliver the fluid as well as the foal. Anneliese quickly reached in to make sure the head was following the feet and not turned back. If necessary, she would have tried to correct the position of the head to allow the birth to proceed.

Now came the hardest part for Tindra–delivering the shoulders. Because one of the foal’s feet was in front of the other, its shoulders were slightly narrowed, making it easier for them to move up and over the mare’s pelvic bone. Tindra’s body was rigid with effort, and she groaned quietly. Anneliese laid a hand on her flank, and when she felt a contraction, she gently pulled out and down on the foal’s feet to, as she says, “add a little pull to the push.”

Once the head and shoulders were delivered, we backed off to give Tindra some privacy and let her rest with her baby. He was collapsed on the ground, all legs and curly, wet fuzzy hair, but his eyes were open, and the tip of his pink tongue was hanging out of the side of his mouth. Within 30 minutes, Tindra was on her feet with the afterbirth hanging from under her tail. Anneliese tied the still-warm membrane in a knot, so it would not drag on the ground. The umbilical cord had broken naturally about one inch from the foal’s belly when his mother stood up. Anneliese held a cup of diluted iodine under his belly and dipped the broken end of the cord to prevent infection. Before the foal began to nurse, Tindra had expelled the placenta, and Anneliese had wormed her.

The new colt was trying to stand as his mother licked and encouraged him. After several attempts, he was shakily upright, using his legs more as straddled supports for his body rather than transferring his weight to his feet. He staggered around the mare trying to manage his legs. She watched him intently. With his tongue wrapped around his upper lip and sucking, he bumped into her legs, her sides, her chest, her nose, and finally into his first taste of milk. After his first meal, the wobbly foal stared at the ground, bent his knees just a bit, rocked too far forward, caught his balance and tried again. He flexed and managed a semi-controlled fall to his knees and collapsed to the ground. Soon, he was stretched out flat on his side, eyes closed, with mother nearby.

About two hours had passed since Tindra had first lain down, and I was exhausted. As we sat at the kitchen table talking about the birth, I felt tears sliding down my cheeks. Tindra had trusted us enough to let us be present and to help her when she and her baby were most vulnerable. The foal’s determination and her tender watchfulness as they touched each other for the first time went straight to my heart. Life went on in the April dark, and I was privileged to be there.

As published in Icelandic Quarterly

We had been taking turns getting up every hour through the early spring nights to check on Tindra. Her udder had been hot and hard for a week, and her due date had come and gone.

We had been taking turns getting up every hour through the early spring nights to check on Tindra. Her udder had been hot and hard for a week, and her due date had come and gone. While Ed never fishes for compliments, we know as an uncle he’s a real catch. He’ll reel you in with his stories in his big bass voice, but won’t tell you a whopper or feed you a line. Now he’s netted eighty years and lured us all here to celebrate.

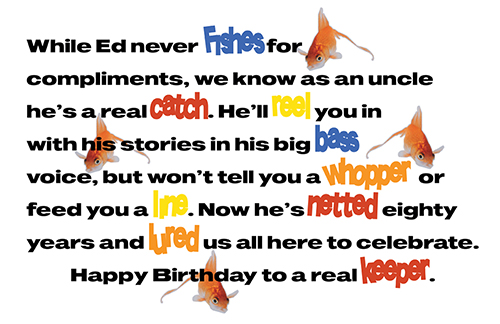

While Ed never fishes for compliments, we know as an uncle he’s a real catch. He’ll reel you in with his stories in his big bass voice, but won’t tell you a whopper or feed you a line. Now he’s netted eighty years and lured us all here to celebrate.